Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

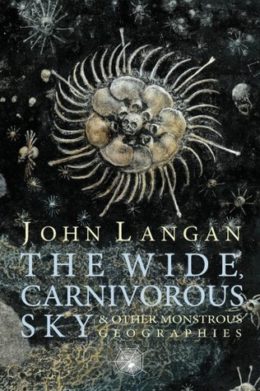

Today we’re looking at John Langan’s “Wide Carnivorous Sky,” first published in John Joseph Adams’s By Blood We Live anthology in 2009. Spoilers ahead.

“Even the soldiers who’d returned from Afghanistan talked about vast forms they’d seen hunched at the crests of mountains; the street in Kabul that usually ended in a blank wall, except when it didn’t; the pale shapes you might glimpse darting into the mouth of the cave you were about to search.”

Summary

So, is it a vampire?

That’s the burning question four Iraq War veterans ask each other over a campfire deep in the Catskills. Narrator Davis, along with Lee, Han and the Lieutenant survived a particularly bloody confrontation in Fallujah, but it wasn’t insurgents who killed the rest of their squad mates and sent them home gravely injured. It was—the Shadow, an eight-foot tall impossibility with a mouthful of fangs, scythe-like claws, collapsible bat-wings and a coffin, or chrysalis, or space-pod in which it spends its nights in low earth orbit. Yes, its nights, because this is a blood-guzzler that walks only when the sun is up.

That day in Fallujah, the Lieutenant’s squad held one end of a courtyard, Iraqi insurgents the other. Into the crossfire descended the Shadow. It first tore apart the Iraqis, draining blood from every wound, oblivious to attack. Then it was the squad’s turn. Davis lucks out—the Shadow flings him into a wall, breaking his spine and putting him out of action while it devotes itself to massacring his mates. The Lieutenant loses a leg. Lee gets clubbed with his own rifle. Before the Shadow can tap him, Han buries his bayonet in its side. Finally, the Shadow’s hurt! It shrieks, elbows Han to the ground, steps on his head and cracks his skull. The last thing Davis sees is the Shadow extruding wings and fleeing into “the washed blue bowl overhead [that] seemed less sheltering canopy and more endless depth, a gullet over which he had the sickening sensation of dangling.”

During his many months of recovery, Davis will remember a weird vision that struck him just before the Shadow’s physical attack, like a preliminary psychic swat: He is suspended in space, above the earth, below a lacquer-glossy house-sized cocoon or ship. His fellow survivors experienced similar but not identical “Shadow-visions.” They decide the thing projects memories to distract its prey and, scarier, that this one psychic connection has established links between their minds and its. At moments of high physical or emotional stress, they’re forced to look through its eyes again, probably to witness another of its feeding frenzies—a situation that tends to undermine PTSD treatment and reintegration into civilian life, for sure.

Involuntarily accompanying the Shadow on one killing spree, Davis finds that anger allows him to disrupt its attack, briefly. Also, that the angered Shadow can then look through his eyes. He starts experimenting with adrenaline, to see if he can induce Shadow-linkup, improve temporary control of its body and its temporary access to his vision. Other survivors join in the effort. They want to lure the Shadow to an isolated place, psychically disable it long enough to ram a hollow “stake” filled with high explosive into it. The reason bullets don’t kill it, they reason, is that they pass straight through the alien substance of its body, which immediately heals afterwards. Han’s bayonet hurt it because it stayed in the wound, kept it open, vulnerable. The stake will do the same. The explosive will finish matters.

They choose Winger Mountain as their isolated place. Each man has a numbered stake and a cell phone. Whoever plants his stake, someone else will dial that number and BOOM. Goodbye, monster. The four wait through a long safe night for the dangerous dawn, speculating. Daybreak, and a red bowl of sky, and the Shadow appears. Lee drives home the first stake, only to be skewered himself. Davis dials Lee’s number, but the explosion comes from Han’s hiding place in the woods. Later the Lieutenant will wonder whether Lee and Han deliberately traded stakes or whether it was an accident—better say the latter. Davis dials Han’s number and is thrown to the ground by a white blast. The world bleeds away….

When it bleeds back, he’s looking at a new black moon. No, he’s staring up the barrel of the Lieutenant’s Glock. Oh, right. One of their last-minute worries had been, what if a dying Shadow could use its psychic connection to leave its wrecked body like a rat deserting a sinking ship for a floating one? In which case, the floating one would need to be scuttled, too. The Lieutenant says the Shadow’s been blown to Kingdom Come. He himself senses no alien crowding in his brain. What about Davis? Think hard. Let him know it’s gone, or let him finish it.

Davis closes his eyes. When he opens them, he assures the Lieutenant that the Shadow is gone from him, no trace. The end of the pistol wavers. Then the Lieutenant helps Davis up. He doesn’t ask what Davis saw with his eyes closed.

Davis doesn’t tell him that it was the same thing he saw with them open. “The unending sky, blue, ravenous.”

What’s Cyclopean: Appropriate to a story about soldiers, the language of this story is harsh and spare—and some of the characters rag on others when they get too multisyllabic.

The Degenerate Dutch: Possibly because the squad are themselves pretty diverse, they manage to avoid any deeply obnoxious comments about the Iraqi locals.

Mythos Making: This is not the first time we’ve seen an alien vampire.

Libronomicon: Our genre-savvy troop draws on Stephen King and Wolverine Versus Sabertooth to understand their situation.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The idea that X hours of combat automatically causes hallucinations is probably BS. The idea that getting attacked by an invulnerable space vampire causes PTSD… is probably not BS.

Anne’s Commentary

So, what’s in a name, or to be more specific to our situation, a title? You can get away with the obvious choice, the minimalist option, say, “Space Vampire.” But since that’s hardly a new concept anymore, you really would be “getting away,” as in the “with a bag of loot in a stolen car” sense. More suitable for your plot bunny notebook: “5/30/18, another idea for Space Vampire thing, fang care in null-gravity???” Or you could go artsy impressionistic, say, “Sirocco Sanguinary.” I don’t know what that means, except it’s got a desert wind thing and a blood thing in it, plus alliterative.

Or you could knock it the hell out of the titling ballpark, as Langan does with this story. In his acknowledgments to the same-titled collection, he credits the phrase “wide, carnivorous sky” to Caitlin Kiernan and her online journals. I haven’t read it in that original context, but all on its own, it’s striking, brilliant, eminently grab-worthy. A wide sky? Nothing new there. But a carnivorous sky? And the piquant contrast between the cliché adjective and the totally unexpected and unnerving one? That a sky should be an EYE, should WATCH, yeah, that I get, that’s been used. That it should be a MOUTH (as “carnivorous” implies), that it should HUNGER, BITE, EAT?

Or that some of its agents should?

One much-discussed aspect of Lovecraftian horror is cosmic indifference toward humanity, since (nooooo!) the cosmos is totally not anthropocentric because not created by anthropomorphic god(s) (God). Lovecraft’s characters often shudder at the mocking aspect of the moon (especially gibbous) and certain stars. In the story brought most to mind by “Wide, Carnivorous Sky”, that is, “The Color Out of Space,” the narrator is troubled by the night sky in general, those starry depths from which such things as ravenous Colors may drop. Come to think, Randolph Carter could tell us much about the ravenous things that live in the spaces between the stars, those larvae of the Outer Gods that float in the aether and nuzzle travelers with much curiosity that might turn to hunger in an instant, yes, precious, it just might, if the travelers are tasty.

A carnivorous sky. A predator sky. To the prey, what could be more Other than the predator? To the soldier, who more Other than the enemy? What place more Other, ironically, than the place called “In Country”? To the four soldiers we meet this week, the Iraqi insurgents pale out of Otherness entirely in comparison with the Shadow. It’s fascinating to “listen” to the comrades speculate about what it is: advance spy, prisoner, devil, Devil. My impression is that none of them has the right answer. They don’t have—can’t take, reasonably—the time to know this creature through longer, deeper psychic contact. Were it even willing to engage in such contact.

No time now, but I’m very much intrigued, this reread, about what is happening with Davis at the end of the story, why he must keep to himself that he sees the wide, carnivorous sky whether his eyes are open or not, whether this implies some connection between him and the Shadow after all, actual or more…metaphoric.

Finally, if anyone should see an ad for a gently used space chrysalis, I’d be interested.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

My plan to compare and contrast “Wide Carnivorous Sky” with “Dust Enforcer” has been stymied by the sheer difference between them. The two share a suspicion that too great a concentration of bloody conflict invites the uncanny, and opens the way to horrors that just might be even scarier than those we can manage on our own. Aside from that, it’s mostly contrast.

At least this week, I have a better idea of what’s going on. I’m just not as excited by it. Langan’s as skilled as ever, both at invoking the creep and keeping the human characters grounded and three-dimensional. But military SF rarely does it for me, and apparently neither does military horror. I’d have been more interested in the space vampire with more emphasis on creepy mind control and less on slaughter and blood-drinking. Langan’s done the mind control part before, in “Children of the Fang,” where I found the merging of human and alien minds both fascinating and unnerving. This one, while disturbing, is a little less effective just because we get no sense of the vampire other than THIRSTY. Which feels either insufficiently alien or insufficiently comprehensible. (Why does the Color take over our bodies? Nobody knows! Why do the Yith take over our bodies? Here’s a 20-page dissertation!)

Maybe for that reason, that moment of paranoia at the end seems the story’s scariest part. The vampire probably hasn’t fully possessed either the Lieutenant or Davis—it just doesn’t seem like it would pass very well. But it might have left shards of itself lodged in their minds, the remnants of that “psychic cluster bomb.” In that case, is the sense of falling into an endlessly hungry sky Davis’s interpretation of the vampire’s mind—the creature confounded with the sky that it so violently drops from? Or is that terror its own experience—part of the punishment or exile that it’s suffering? And what does it mean, either way, if Davis can no longer escape from that perception?

Setting this during the Iraq War, with American soldiers, is an interesting take on cosmic horror. The core of cosmic horror is that no place, no civilization, is safe or special. Dagon follows his witness home. Horror hides behind rural facades, in the depths of cities, and in the most remote wilderness. But America’s wars of the last few decades have been distanced dangers. As Davis points out, weird shit happens Over There, and all the soldiers’ campfire stories only serve to emphasize that disconnect. And the vampire, indeed, prefers conflict zones where its depredations can be camouflaged. In its shared memories, the closest it gets to the American heartland is the US-Mexico border. Refugees also make an easy target, one supposes, violence against them unlikely to be investigated.

Notable, then, that the Lieutenant is himself a Mexican immigrant. And gets the job done.

And, to do that, brings the vampire down in the Catskills. Not exactly a conflict zone, even if it is bat country Mi-go country. Maybe we can’t solve these problems until we let them touch our home turf? Or maybe a bunch of traumatized veterans just needed an isolated patch of land, relatively close to home, to finish the thing.

Next week, Tim Pratt’s “Cinderlands” suggests that rats in the walls are a particular issue if you’re renting. You can find it in The Book of Cthulhu.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

The title brought to my mind the giant invisible “skymouths” in Fran Wilde’s Bone Universe books, but it turns out to be about something rather different.

Oh yes, Wilde’s skymouths do render the airy heights carnivorous. They are some very scary beasts, and I love them.

You would think that MilHorror would be more common, but it seems to me that when military issues are involved, the horror mostly takes place back home than on the battlefield or in the trenches. Off the top of my head, and I’m admittedly not all that well-versed, the only example I can think of is The Keep, and even that’s behind the lines.

@anne: Since the sirocco is Saharan, perhaps Haboob Hematophage in this case?

Next week’s story can also be heard on Drabblecast episode 176.

@3: Dog Soldiers and Frankenstein’s Army come to mind, though I haven’t seen either of them. Perhaps military horror is more common as a cinematic form than a literary one?

@3:@anne: Since the sirocco is Saharan, perhaps Haboob Hematophage in this case?

I’d suggest Simoom, it’s more Middle-Eastern, and has the bonus of meaning Poison Wind.